read an excerpt

Chasing Tomorrow

BEGINNING

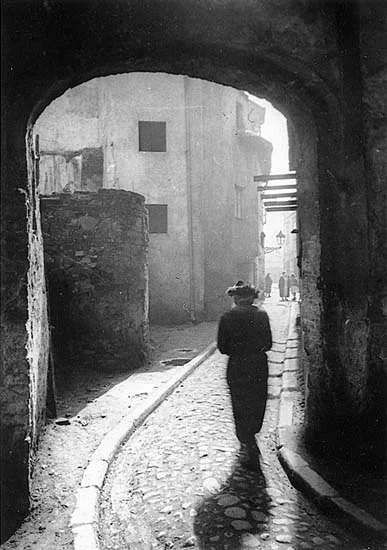

Voynilov, Poland – 1936

“Voynilov isn’t a place you’d ever go for a visit,” my father began, setting the stage. Not even now, with all those people trying to protect all the ruined buildings, telling everyone how important they are on those walking tours. It makes me laugh, seeing those ladies in high heels on a hot day with flags on the end of their umbrellas, twenty or thirty people following behind, ooh-ing and ah-ing like it’s the Taj Mahal. And outside those crummy buildings, a bunch of peasants, all selling the same miniature replicas of those bombed out places, probably made in China. They were ruins then too, so what’s to protect? But some people think that is interesting stuff. Anyway, it was a very small town, a village really. There was a Jewish temple of course, with a cemetery, and also a church, some houses all painted white with brown or green shutters and vegetable gardens in front, a few farms and shops, nothing special. I don’t think even a thousand people lived there.

Just outside Voynilov to the west is the Dniester River which is very large and scenic, so if someone comes into town that way or maybe to go for a picnic, which I never did, you could take advantage of the view. There were always people out walking, horses pulling buggies, maybe a few old women sweeping dirt off their porches, trying to avoid the feet of their old husbands sitting there, kids playing, a stray dog or two. It was about five hundred kilometers west of Kiev, very close to what is now the Polish border. At the time, it was Poland there, not Ukraine like now, but who cares? It’s just a dot on a map. In fact, it isn’t even on most maps, just a little shtetl in the middle of nowhere. But I didn’t know that. To me it was home. Not exciting, not boring, just an ordinary place anyone would live. It was 1936 and I was thirteen years old.

My father, Rakhmil, was a simple man, stern, but gentle in his way, a tailor. He never raised his voice. He didn’t have to because I could always tell when he was upset. One time, on a very cold night, I forgot to bring in the firewood early enough and it got too wet to burn continuously without going out. He got a sharp look in his eyes and stared down his long nose at me.

“I am disappointed.”

“I’m sorry Papa.”

“We will all be cold tonight.”

“It won’t happen again.”

“You will be sleeping next to the fire tonight and whenever it goes out, you will add more wood and relight it, all night long. Now go apologize to your mother.”

“Yes, Papa,” and off I went.

He nodded and returned to reading his paper. If he was really angry, he would start off by telling me that it was his responsibility to provide for me and my responsibility to do as he said, not to question him, and never to be disrespectful to my mother. It was enough. I got the message and that was that. He wouldn’t say another word and the matter, whatever it was, would be resolved.

He spent his days working in the tailor shop, chatting with the other merchants, drinking black tea and reading the newspaper. He was tall and slender, a full dark beard and always a karakul on his head, like a member of the Politburo in Moscow. It was made of black, curly, Persian lamb fur, very warm and stylish. All of the men wore them. My father made them to sell to a few of his tailoring customers. It was a hobby he did in his spare time to make some extra money when he wasn’t smoking his pipe or reading the Torah.

My mother Klyara, on the other hand, was a makhashaifeh, a holy terror. She was always complaining, never a kind word for anyone. No matter how hard I tried to please her, it didn’t matter. She picked on me, my little sister Malka and my father too, but never on my brother. One morning she came into the room I shared with my brother and poked me in the ribs with the end of her broom while my brother lay sleeping undisturbed in the other bed.

“Zygmunt, get up! Why are you still lying there?”

“What is it Mama? It’s the middle of the night. It’s dark outside.”

“There’s work to be done! Did you feed the goats from this bed?”

“No, Mama, I was sleeping.”

“Do you think they can wait all day?”

“I’m sorry, I’m getting up right now, but can I have a little tea before I go out in the cold?”

She called over her shoulder to my father who was in the other room, “Rakhmil, are you listening to this? Do you hear how he talks to me, this little shmendrick?”

“I only hear you shouting at him,” he said with a sigh.

She started out of my room, probably to yell at my father, but then she spotted my little sister Malka hiding in the corner.

“Go fix yourself up,” she said, “You look like a goat with your mouth open like that.”

“Sorry Mama,” she whispered, her lips starting to tremble.

This time my father had heard enough. He didn’t usually interfere, but when he heard my sister start to cry, he rose from the table and walked over.

“Klyara,” he said quietly, “Please stop yelling at her. Can’t you see how upset she is?”

Sometimes my mother softened a little when he tried to reason with her, but usually, it just made her angrier.

“How dare you?” she said to him, “See with your own eyes, such a chazer she is, she should sleep with the other pigs.”

“She’s just a child, they both are.”

“Shut up,” she shouted at him, “You are no better.”

“Vus vilste frun mein leiben? Do you want I should slice open my arm and give you my blood?”

“Go work, make some money.”

“I am trying hard every day.”

“Try harder.”

“Such a klippeh you are, nagging me all the time.”

“What Rakhmil? What did you say?”

“Nothing, nothing,” he said turning away, knowing he wasn’t going to win that argument. He returned to the kitchen and his reading. Meanwhile, the whole time this was going on, my brother just stayed in bed, put the pillow over his head and went back to sleep. I never knew what was coming next, but whatever it was, I wasn’t surprised. That’s just how she was—a wild red haired shrew.

And so, we lived. We had enough to eat, a pair of shoes and sometimes, maybe for Hanukkah, a piece of chocolate. When it wasn’t too cold I went to school, did my Torah studies, and tried to stay out of my mother’s way. Around this time, I started learning tailoring to help my father in the tailor shop. He needed my help because he had a bullet hole in his right arm and he suffered from it. Sometimes, if it was very cold or raining, he couldn’t work at all. My father was born in Austria and he had been a soldier in the Austrian Army in World War I. Germany and Austria were allies in those days, so he got that bullet hole defending Germany, defending the Fatherland. He didn’t complain. He was proud of his military service and wore his injury like a man who had won a prize.

By the time I was fifteen, I was a pretty good tailor and my father was very proud of me. My brother on the other hand, was a lazy good-for-nothing, always pouting and complaining. Even though he was the bechor and should have been the one to help my father and take over the shop, he refused. He was too high and mighty to learn tailoring. He was always talking about America, how he would go there and get rich, leave all this misery behind, such a dreamer he was, and I was a good tailor. One evening, my brother was being even nastier than usual and even though we were still sitting at the kitchen table eating dinner, usually one of the few relaxing times of the day, he turned to my father with a nasty look on his face.

“Papa, we have bupkis,” his voice was loud and angry.

“Why you don’t do something to help?”

“Why should I?” he answered, staring defiantly at my father.

“Your grandfather is turning over in his grave hearing you say such awful things.”

“Who cares?”

“Oy Gotenyu! God should help us, such talk.”

“This place is awful, I can’t wait to leave.”

“How you can say this to me? This is how you talk to your Papa?

Why don’t you have any respect?”

“You sit here, just like your father, waiting for tsurris to come along and knock on the door.”

“Oy vey, I should give you a zetz in punim, your face should sting like these arrows you are shooting into my guts.”

“You are supposed to be taking care of me Papa, taking care of everything, not the other way around.”

“And you give me a shtuken nisht in hartz,” my father said, grabbing his chest for emphasis and holding up his arm pretending to plunge the knife into his heart.

“You expect me to thank you?”

“You are like a drunk, so mixed up in the head you are.”

“And you have your head in the sand.”

”Let me tell you a story about Shlomo.” My father was always with his teaching stories.

“Another one of your bubbe maisehs Papa?” my brother interrupted, “I am sick of them.”

“Maybe you can learn something,” he said.

But my brother wasn’t interested. Even though we had heard those old wives tales many times before, I liked to hear them over and over. My father would settle into his chair, pipe in hand, and begin the story in his rich baritone voice, always adding something new to it, usually for the sake of the lesson he was trying to teach. For me, it was a chance to sit at my father’s feet, listening and imagining as he spoke. For my brother it was a punishment and he would twist around instead of sitting quietly, while tapping his foot all broygus and sullen, just glaring at my father.

“It was very crowded in Shlomo’s house,” my father began. “Ten children, a wife, a mother-in-law, and two cousins all living in a one room house with a dirt floor. No running water and a drafty, filthy outhouse. In the winter, when it was too cold to go outside during the night to use the toilet, he kept a bucket inside which made the place smell even worse. It was a dirty, freezing, wretched place and Shlomo was miserable. One day he went to see the rabbi.

“Rabbi Jacobs,” Shlomo said, “It is so awful in my house I cannot stand living there anymore. I have no privacy, it is never quiet, it stinks like hell, someone is always crying or complaining and there is never what to eat. Please Rabbi, help me, what can I do?”

“Get the goat and bring him into the house,” the rabbi instructed.

Shlomo thought he was hearing things. “The goat?” he said, “Bring him into the house for what?”

“To live with you,” the rabbi said solemnly.

“You want I should bring the goat inside to live?”

“Yes Shlomo that will solve all of your problems.”

Shlomo was confused but he didn’t question the rabbi. He just went home and brought the goat into the house. Now that was a disaster! The goat ate the furniture, shat in the kitchen, and made noises all night long. His wife was even worse than before, yelling at him all the time about die stinkende ziegen, and how he better watch out because she is going to kill that stinking goat and maybe him too, what’s the matter with him, is he crazy? There was no peace. It was terrible. After a few weeks of this, Shlomo went back to the rabbi, hat in hand.

“Rabbi, when I came to see you before, you told me to bring the goat into the house to live. You said it would solve my problems, but it is much worse than before. We are awake all night, arguing, yelling, it stinks like something died, and the goat is destroying everything.”

“Take the goat out of the house and put him back in the barn,” was the rabbi’s advice.

“Now you want I should take the goat back to the barn?”

“Yes, take him back, that’s the solution, trust me.”

Shlomo shook his head, still not understanding, but he went home and took the goat back to the barn. At the next Shabbat service, Rabbi Jacobs saw Shlomo. He was standing with some other men, laughing and talking. The rabbi hadn’t seen him that happy in years.

“Shlomo,” he said, “I see you are very happy.”

“Rabbi, ad meah v’esrim shanah, may you live to be 120!

“Things are better at home? Yes?”

“You are baal Torah, such a brilliant man, you changed my life.”

“Tell me Shlomo, what has changed?”

“After I went home and took the goat out, all of our problems were solved! It is so quiet in the house, it smells like roses and we haven’t had another thing broken.”

“This is wonderful news!” the rabbi clapped him on the shoulder.

“My wife and I are chattering like lovebirds, and everyone is sleeping so much better.”

“So,” the rabbi said, “Altz is gut and you are fine?”

“Yes, yes, it is wonderful now, and we are so happy.”

“Danken Got!” he said, looking up to heaven while Shlomo slipped a few shekels into Rabbi Jacobs’ pocket, “Such a miracle as this only God can perform!”

When the story was finished, my father liked to talk about the meaning, making his point again in case we missed it. But this time, my brother got up and left the room before he could say another word. So my father just sat there, looking at where my brother had been sitting as if he were still there, then he sighed, shook his head sadly, and held his face in his hands.

And so it went. But no matter how hard my father tried to reason with him, it was not enough to change my brother’s mind and that broke my father’s heart. Of course, you might be wondering how my brother could have such chutzpah to speak to my father this way. Well the truth is that he was my mother’s favorite. Never my father should say something against my brother that my mother shouldn’t stick up for him. Her little baby boychik could do no wrong. He was not to be blamed; he was a victim of circumstances, I think you say.

Oy Gevalt! Such a pain in the ass he was, always complaining, not doing a thing to help my father, and my mother always protecting him. Nothing changed much until March of 1938 when my father decided to send my brother to America to live with my Aunt Tillie, my mother’s sister. If you had a sponsor, someone that was willing to claim you once you got there, you could go to America and they would let you in. I think it was to get rid of him because he was such a troublemaker, but my father said it was for opportunity. Probably my mother insisted, who knows? Even after all the heartache my brother had caused, my father still bought him a ticket and sent him. He said it was because my brother was the oldest, that he should be the one to go and pick up the gold laying in the streets. He would be there waiting to welcome us when we got there. Someday soon we would all go, he promised. Boy-oh-boy was he ever wrong about that!

You see, my father was a wise man, but he was not worldly. He thought we were going to be fine, protected even. Why he thought this? Why not? He was an honest man living in a small town in the middle of nowhere, minding his own business, and besides—he was a German Army veteran, a decorated soldier who had served his country. It never occurred to him that everything was changing or that we could become targets. We had heard the talk, “Hitler this, Hitler that,” but my father didn’t believe the rumors about all the trouble brewing in Germany about Hitler’s ambitions, or the possibility that it would actually come to us. No one did.

Rakhmil and Klyara 1919

Comments?

Malke, Zygmunt, Marcus - 1928